Reading in data locally and from the web

Contents

Reading in data locally and from the web¶

We need to import the pandas package in order to read data into Python

import pandas as pd

import warnings

warnings.filterwarnings('ignore')

Overview¶

In this chapter, you’ll learn to read tabular data of various formats into Python from your local device (e.g., your laptop) and the web. “Reading” (or “loading”) \index{loading|see{reading}}\index{reading!definition} is the process of converting data (stored as plain text, a database, HTML, etc.) into an object (e.g., a data frame) that Python can easily access and manipulate. Thus reading data is the gateway to any data analysis; you won’t be able to analyze data unless you’ve loaded it first. And because there are many ways to store data, there are similarly many ways to read data into Python. The more time you spend upfront matching the data reading method to the type of data you have, the less time you will have to devote to re-formatting, cleaning and wrangling your data (the second step to all data analyses). It’s like making sure your shoelaces are tied well before going for a run so that you don’t trip later on!

Chapter learning objectives¶

By the end of the chapter, readers will be able to do the following:

Define the following:

absolute file path

relative file path

Uniform Resource Locator (URL)

Read data into Python using an absolute path, relative path and a URL.

Compare and contrast the following functions:

read_csvread_tableread_excel

Match the following

pandas.read_*function arguments to their descriptions:filepath_or_buffersepnamesskiprows

Choose the appropriate

pandas.read_*function and function arguments to load a given plain text tabular data set into Python.Use

pandaspackage’sread_excelfunction and arguments to load a sheet from an excel file into Python.Connect to a database using the

SQLAlchemylibrary.List the tables in a database using

SQLAlchemylibrary’stable_namesfunctionCreate a reference to a database table that is queriable using the

SQLAlchemylibrary’sselectandwherefunctionsUse

.to_csvto save a data frame to a csv file(Optional) Obtain data using application programming interfaces (APIs) and web scraping.

Read/scrape data from an internet URL using the

BeautifulSouppackageCompare downloading tabular data from a plain text file (e.g. *.csv) from the web versus scraping data from a .html file

Absolute and relative file paths¶

This chapter will discuss the different functions we can use to import data into Python, but before we can talk about how we read the data into Python with these functions, we first need to talk about where the data lives. When you load a data set into Python, you first need to tell Python where those files live. The file could live on your computer (local) \index{location|see{path}} \index{path!local, remote, relative, absolute} or somewhere on the internet (remote).

The place where the file lives on your computer is called the “path”. You can think of the path as directions to the file. There are two kinds of paths: relative paths and absolute paths. A relative path is where the file is with respect to where you currently are on the computer (e.g., where the file you’re working in is). On the other hand, an absolute path is where the file is in respect to the computer’s filesystem base (or root) folder.

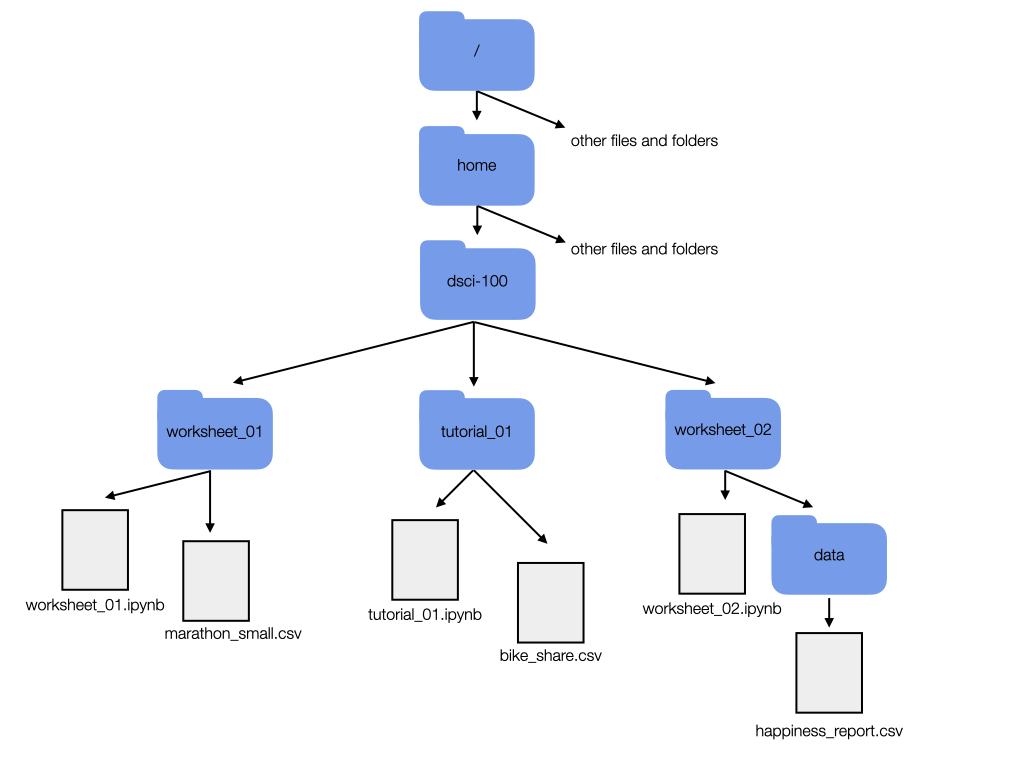

Suppose our computer’s filesystem looks like the picture in

Fig. 9, and we are working in a

file titled worksheet_02.ipynb. If we want to

read the .csv file named happiness_report.csv into Python, we could do this

using either a relative or an absolute path. We show both choices

below.\index{Happiness Report}

Fig. 9 Example file system¶

Reading happiness_report.csv using a relative path:

happy_data = pd.read_csv("data/happiness_report.csv")

Reading happiness_report.csv using an absolute path:

happy_data = pd.read_csv("/home/dsci-100/worksheet_02/data/happiness_report.csv")

So which one should you use? Generally speaking, to ensure your code can be run

on a different computer, you should use relative paths. An added bonus is that

it’s also less typing! Generally, you should use relative paths because the file’s

absolute path (the names of

folders between the computer’s root / and the file) isn’t usually the same

across different computers. For example, suppose Fatima and Jayden are working on a

project together on the happiness_report.csv data. Fatima’s file is stored at

/home/Fatima/project/data/happiness_report.csv,

while Jayden’s is stored at

/home/Jayden/project/data/happiness_report.csv.

Even though Fatima and Jayden stored their files in the same place on their

computers (in their home folders), the absolute paths are different due to

their different usernames. If Jayden has code that loads the

happiness_report.csv data using an absolute path, the code won’t work on

Fatima’s computer. But the relative path from inside the project folder

(data/happiness_report.csv) is the same on both computers; any code that uses

relative paths will work on both!

Your file could be stored locally, as we discussed, or it could also be somewhere on the internet (remotely). A Uniform Resource Locator (URL) (web address) \index{URL} indicates the location of a resource on the internet and helps us retrieve that resource. Next, we will discuss how to get either locally or remotely stored data into Python.

Reading tabular data from a plain text file into Python¶

read_csv to read in comma-separated files {#readcsv}¶

Now that we have learned about where data could be, we will learn about how

to import data into Python using various functions. Specifically, we will learn how

to read tabular data from a plain text file (a document containing only text)

into Python and write tabular data to a file out of Python. The function we use to do this

depends on the file’s format. For example, in the last chapter, we learned about using

the pandas read_csv function when reading .csv (comma-separated values)

files. \index{csv} In that case, the separator or delimiter \index{reading!delimiter} that divided our columns was a

comma (,). We only learned the case where the data matched the expected defaults

of the read_csv function \index{read function!read_csv}

(column names are present, and commas are used as the delimiter between columns).

In this section, we will learn how to read

files that do not satisfy the default expectations of read_csv.

Before we jump into the cases where the data aren’t in the expected default format

for pandas and read_csv, let’s revisit the more straightforward

case where the defaults hold, and the only argument we need to give to the function

is the path to the file, data/can_lang.csv. The can_lang data set contains

language data from the 2016 Canadian census. \index{Canadian languages!canlang data}

We put data/ before the file’s

name when we are loading the data set because this data set is located in a

sub-folder, named data, relative to where we are running our Python code.

Here is what the file would look like in a plain text editor (a program that removes all formatting, like bolding or different fonts):

category,language,mother_tongue,most_at_home,most_at_work,lang_known

Aboriginal languages,"Aboriginal languages, n.o.s.",590,235,30,665

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages,Afrikaans,10260,4785,85,23415

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages,"Afro-Asiatic languages, n.i.e.",1150,44

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages,Akan (Twi),13460,5985,25,22150

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages,Albanian,26895,13135,345,31930

Aboriginal languages,"Algonquian languages, n.i.e.",45,10,0,120

Aboriginal languages,Algonquin,1260,370,40,2480

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages,American Sign Language,2685,3020,1145,21

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages,Amharic,22465,12785,200,33670

And here is a review of how we can use read_csv to load it into Python. First we

load the pandas \index{tidyverse} package to gain access to useful

functions for reading the data.

Next we use read_csv to load the data into Python, and in that call we specify the

relative path to the file.

canlang_data = pd.read_csv("data/can_lang.csv")

canlang_data

| category | language | mother_tongue | most_at_home | most_at_work | lang_known | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Aboriginal languages | Aboriginal languages, n.o.s. | 590 | 235 | 30 | 665 |

| 1 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Afrikaans | 10260 | 4785 | 85 | 23415 |

| 2 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Afro-Asiatic languages, n.i.e. | 1150 | 445 | 10 | 2775 |

| 3 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Akan (Twi) | 13460 | 5985 | 25 | 22150 |

| 4 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Albanian | 26895 | 13135 | 345 | 31930 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 209 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Wolof | 3990 | 1385 | 10 | 8240 |

| 210 | Aboriginal languages | Woods Cree | 1840 | 800 | 75 | 2665 |

| 211 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Wu (Shanghainese) | 12915 | 7650 | 105 | 16530 |

| 212 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Yiddish | 13555 | 7085 | 895 | 20985 |

| 213 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Yoruba | 9080 | 2615 | 15 | 22415 |

214 rows × 6 columns

Skipping rows when reading in data¶

Oftentimes, information about how data was collected, or other relevant information, is included at the top of the data file. This information is usually written in sentence and paragraph form, with no delimiter because it is not organized into columns. An example of this is shown below. This information gives the data scientist useful context and information about the data, however, it is not well formatted or intended to be read into a data frame cell along with the tabular data that follows later in the file.

Data source: https://ttimbers.github.io/canlang/

Data originally published in: Statistics Canada Census of Population 2016.

Reproduced and distributed on an as-is basis with their permission.

category,language,mother_tongue,most_at_home,most_at_work,lang_known

Aboriginal languages,"Aboriginal languages, n.o.s.",590,235,30,665

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages,Afrikaans,10260,4785,85,23415

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages,"Afro-Asiatic languages, n.i.e.",1150,44

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages,Akan (Twi),13460,5985,25,22150

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages,Albanian,26895,13135,345,31930

Aboriginal languages,"Algonquian languages, n.i.e.",45,10,0,120

Aboriginal languages,Algonquin,1260,370,40,2480

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages,American Sign Language,2685,3020,1145,21

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages,Amharic,22465,12785,200,33670

With this extra information being present at the top of the file, using

read_csv as we did previously does not allow us to correctly load the data

into Python. In the case of this file we end up only reading in one column of the

data set:

canlang_data = pd.read_csv("data/can_lang-meta-data.csv")

ParserError: Error tokenizing data. C error: Expected 3 fields in line 3, saw 6

Note: In contrast to the normal and expected messages above, this time Python printed out a Parsing error for us indicating that there might be a problem with how our data is being read in. \index{warning}

To successfully read data like this into Python, the skiprows

argument \index{read function!skip argument} can be useful to tell Python

how many lines to skip before

it should start reading in the data. In the example above, we would set this

value to 2 and pass header as None to read and load the data correctly.

canlang_data = pd.read_csv("data/can_lang-meta-data.csv", skiprows=2, header=None)

canlang_data

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Aboriginal languages | Aboriginal languages, n.o.s. | 590 | 235 | 30 | 665 |

| 1 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Afrikaans | 10260 | 4785 | 85 | 23415 |

| 2 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Afro-Asiatic languages, n.i.e. | 1150 | 445 | 10 | 2775 |

| 3 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Akan (Twi) | 13460 | 5985 | 25 | 22150 |

| 4 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Albanian | 26895 | 13135 | 345 | 31930 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 423 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Wolof | 3990 | 1385 | 10 | 8240 |

| 424 | Aboriginal languages | Woods Cree | 1840 | 800 | 75 | 2665 |

| 425 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Wu (Shanghainese) | 12915 | 7650 | 105 | 16530 |

| 426 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Yiddish | 13555 | 7085 | 895 | 20985 |

| 427 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Yoruba | 9080 | 2615 | 15 | 22415 |

428 rows × 6 columns

How did we know to skip two lines? We looked at the data! The first two lines of the data had information we didn’t need to import:

Source: Statistics Canada, Census of Population, 2016. Reproduced and distributed on an "as is" basis with the permission of Statistics Canada.

Date collected: 2020/07/09

The column names began at line 3, so we skipped the first two lines.

read_csv with sep argument to read in tab-separated files¶

Another common way data is stored is with tabs as the delimiter. Notice the

data file, can_lang.tsv, has tabs in between the columns instead of

commas.

category language mother_tongue most_at_home most_at_work lang_kno

Aboriginal languages Aboriginal languages, n.o.s. 590 235 30 665

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages Afrikaans 10260 4785 85 23415

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages Afro-Asiatic languages, n.i.e. 1150

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages Akan (Twi) 13460 5985 25 22150

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages Albanian 26895 13135 345 31930

Aboriginal languages Algonquian languages, n.i.e. 45 10 0 120

Aboriginal languages Algonquin 1260 370 40 2480

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages American Sign Language 2685 3020

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages Amharic 22465 12785 200 33670

To read in this type of data, we can use the read_csv with sep argument

\index{tab-separated values|see{tsv}}\index{tsv}\index{read function!read_tsv}

to read in .tsv (tab separated values) files.

canlang_data = pd.read_csv("data/can_lang.tsv", sep="\t", header=None)

canlang_data

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Aboriginal languages | Aboriginal languages, n.o.s. | 590 | 235 | 30 | 665 |

| 1 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Afrikaans | 10260 | 4785 | 85 | 23415 |

| 2 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Afro-Asiatic languages, n.i.e. | 1150 | 445 | 10 | 2775 |

| 3 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Akan (Twi) | 13460 | 5985 | 25 | 22150 |

| 4 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Albanian | 26895 | 13135 | 345 | 31930 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 209 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Wolof | 3990 | 1385 | 10 | 8240 |

| 210 | Aboriginal languages | Woods Cree | 1840 | 800 | 75 | 2665 |

| 211 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Wu (Shanghainese) | 12915 | 7650 | 105 | 16530 |

| 212 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Yiddish | 13555 | 7085 | 895 | 20985 |

| 213 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Yoruba | 9080 | 2615 | 15 | 22415 |

214 rows × 6 columns

Let’s compare the data frame here to the resulting data frame in Section

@ref(readcsv) after using read_csv. Notice anything? They look the same! The

same number of columns/rows and column names! So we needed to use different

tools for the job depending on the file format and our resulting table

(canlang_data) in both cases was the same!

read_table as a more flexible method to get tabular data into Python¶

read_csv and read_csv with argument sep are actually just special cases of the more general

read_table \index{read function!read_delim} function. We can use

read_table to import both comma and tab-separated files (and more), we just

have to specify the delimiter. The can_lang.tsv is a different version of

this same data set with no column names and uses tabs as the delimiter

\index{reading!delimiter} instead of commas.

Here is how the file would look in a plain text editor:

Aboriginal languages Aboriginal languages, n.o.s. 590 235 30 665

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages Afrikaans 10260 4785 85 23415

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages Afro-Asiatic languages, n.i.e. 1150

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages Akan (Twi) 13460 5985 25 22150

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages Albanian 26895 13135 345 31930

Aboriginal languages Algonquian languages, n.i.e. 45 10 0 120

Aboriginal languages Algonquin 1260 370 40 2480

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages American Sign Language 2685 3020

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages Amharic 22465 12785 200 33670

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages Arabic 419890 223535 5585 629055

To get this into Python using the read_table function, we specify the first

argument as the path to the file (as done with read_csv), and then provide

values to the sep \index{read function!delim argument} argument (here a

tab, which we represent by "\t").

Note:

\tis an example of an escaped character, which always starts with a backslash (\). \index{escape character} Escaped characters are used to represent non-printing characters (like the tab) or characters with special meanings (such as quotation marks).

canlang_data = pd.read_csv("data/can_lang.tsv",

sep = "\t",

header = None)

canlang_data

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Aboriginal languages | Aboriginal languages, n.o.s. | 590 | 235 | 30 | 665 |

| 1 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Afrikaans | 10260 | 4785 | 85 | 23415 |

| 2 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Afro-Asiatic languages, n.i.e. | 1150 | 445 | 10 | 2775 |

| 3 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Akan (Twi) | 13460 | 5985 | 25 | 22150 |

| 4 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Albanian | 26895 | 13135 | 345 | 31930 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 209 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Wolof | 3990 | 1385 | 10 | 8240 |

| 210 | Aboriginal languages | Woods Cree | 1840 | 800 | 75 | 2665 |

| 211 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Wu (Shanghainese) | 12915 | 7650 | 105 | 16530 |

| 212 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Yiddish | 13555 | 7085 | 895 | 20985 |

| 213 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Yoruba | 9080 | 2615 | 15 | 22415 |

214 rows × 6 columns

Data frames in Python need to have column names. Thus if you read in data that

don’t have column names, Python will assign names automatically. In the example

above, Python assigns each column a name of 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5.

It is best to rename your columns to help differentiate between them

(e.g., 0, 1, etc., are not very descriptive names and will make it more confusing as

you code). To rename your columns, you can use the rename function

\index{rename} from the pandas package.

The argument of the rename function is columns, which is a dictionary,

where the keys are the old column names and values are the new column names.

We rename the old 0, 1, ..., 5

columns in the canlang_data data frame to more descriptive names below, with the

inplace argument as True, so that the columns are renamed in place.

canlang_data.rename(columns = {0:'category',

1:'language',

2:'mother_tongue',

3:'most_at_home',

4:'most_at_work',

5:'lang_known'}, inplace = True)

canlang_data

| category | language | mother_tongue | most_at_home | most_at_work | lang_known | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Aboriginal languages | Aboriginal languages, n.o.s. | 590 | 235 | 30 | 665 |

| 1 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Afrikaans | 10260 | 4785 | 85 | 23415 |

| 2 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Afro-Asiatic languages, n.i.e. | 1150 | 445 | 10 | 2775 |

| 3 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Akan (Twi) | 13460 | 5985 | 25 | 22150 |

| 4 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Albanian | 26895 | 13135 | 345 | 31930 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 209 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Wolof | 3990 | 1385 | 10 | 8240 |

| 210 | Aboriginal languages | Woods Cree | 1840 | 800 | 75 | 2665 |

| 211 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Wu (Shanghainese) | 12915 | 7650 | 105 | 16530 |

| 212 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Yiddish | 13555 | 7085 | 895 | 20985 |

| 213 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Yoruba | 9080 | 2615 | 15 | 22415 |

214 rows × 6 columns

The column names can also be assigned to the dataframe while reading it from the file by passing a

list of column names to the names argument. read_csv and read_table have a names argument,

\index{read function!col_names argument} whose default value is [].

canlang_data = pd.read_csv("data/can_lang.tsv",

sep = "\t",

header = None,

names = ['category', 'language', 'mother_tongue', 'most_at_home', 'most_at_work', 'lang_known'])

canlang_data

| category | language | mother_tongue | most_at_home | most_at_work | lang_known | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Aboriginal languages | Aboriginal languages, n.o.s. | 590 | 235 | 30 | 665 |

| 1 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Afrikaans | 10260 | 4785 | 85 | 23415 |

| 2 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Afro-Asiatic languages, n.i.e. | 1150 | 445 | 10 | 2775 |

| 3 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Akan (Twi) | 13460 | 5985 | 25 | 22150 |

| 4 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Albanian | 26895 | 13135 | 345 | 31930 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 209 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Wolof | 3990 | 1385 | 10 | 8240 |

| 210 | Aboriginal languages | Woods Cree | 1840 | 800 | 75 | 2665 |

| 211 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Wu (Shanghainese) | 12915 | 7650 | 105 | 16530 |

| 212 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Yiddish | 13555 | 7085 | 895 | 20985 |

| 213 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Yoruba | 9080 | 2615 | 15 | 22415 |

214 rows × 6 columns

Reading tabular data directly from a URL¶

We can also use read_csv, read_table(and related functions)

to read in data directly from a Uniform Resource Locator (URL) that

contains tabular data. \index{URL!reading from} Here, we provide the URL to

read_* as the path to the file instead of a path to a local file on our

computer. We need to surround the URL with quotes similar to when we specify a

path on our local computer. All other arguments that we use are the same as

when using these functions with a local file on our computer.

url = "https://raw.githubusercontent.com/UBC-DSCI/introduction-to-datascience-python/reading/source/data/can_lang.csv"

pd.read_csv(url)

canlang_data = pd.read_csv(url)

canlang_data

| category | language | mother_tongue | most_at_home | most_at_work | lang_known | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Aboriginal languages | Aboriginal languages, n.o.s. | 590 | 235 | 30 | 665 |

| 1 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Afrikaans | 10260 | 4785 | 85 | 23415 |

| 2 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Afro-Asiatic languages, n.i.e. | 1150 | 445 | 10 | 2775 |

| 3 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Akan (Twi) | 13460 | 5985 | 25 | 22150 |

| 4 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Albanian | 26895 | 13135 | 345 | 31930 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 209 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Wolof | 3990 | 1385 | 10 | 8240 |

| 210 | Aboriginal languages | Woods Cree | 1840 | 800 | 75 | 2665 |

| 211 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Wu (Shanghainese) | 12915 | 7650 | 105 | 16530 |

| 212 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Yiddish | 13555 | 7085 | 895 | 20985 |

| 213 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Yoruba | 9080 | 2615 | 15 | 22415 |

214 rows × 6 columns

Previewing a data file before reading it into Python¶

In all the examples above, we gave you previews of the data file before we read it into Python. Previewing data is essential to see whether or not there are column names, what the delimiters are, and if there are lines you need to skip. You should do this yourself when trying to read in data files. You can preview files in a plain text editor by right-clicking on the file, selecting “Open With,” and choosing a plain text editor (e.g., Notepad).

Reading tabular data from a Microsoft Excel file¶

There are many other ways to store tabular data sets beyond plain text files,

and similarly, many ways to load those data sets into Python. For example, it is

very common to encounter, and need to load into Python, data stored as a Microsoft

Excel \index{Excel spreadsheet}\index{Microsoft Excel|see{Excel

spreadsheet}}\index{xlsx|see{Excel spreadsheet}} spreadsheet (with the file name

extension .xlsx). To be able to do this, a key thing to know is that even

though .csv and .xlsx files look almost identical when loaded into Excel,

the data themselves are stored completely differently. While .csv files are

plain text files, where the characters you see when you open the file in a text

editor are exactly the data they represent, this is not the case for .xlsx

files. Take a look at a snippet of what a .xlsx file would look like in a text editor:

,?'O

_rels/.rels???J1??>E?{7?

<?V????w8?'J???'QrJ???Tf?d??d?o?wZ'???@>?4'?|??hlIo??F

t 8f??3wn

????t??u"/

%~Ed2??<?w??

?Pd(??J-?E???7?'t(?-GZ?????y???c~N?g[^_r?4

yG?O

?K??G?

]TUEe??O??c[???????6q??s??d?m???\???H?^????3} ?rZY? ?:L60?^?????XTP+?|?

X?a??4VT?,D?Jq

This type of file representation allows Excel files to store additional things

that you cannot store in a .csv file, such as fonts, text formatting,

graphics, multiple sheets and more. And despite looking odd in a plain text

editor, we can read Excel spreadsheets into Python using the pandas package’s read_excel

function developed specifically for this

purpose. \index{readxl}\index{read function!read_excel}

canlang_data = pd.read_excel("data/can_lang.xlsx")

canlang_data

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

ModuleNotFoundError Traceback (most recent call last)

File /opt/miniconda3/envs/dsci100/lib/python3.9/site-packages/pandas/compat/_optional.py:138, in import_optional_dependency(name, extra, errors, min_version)

137 try:

--> 138 module = importlib.import_module(name)

139 except ImportError:

File /opt/miniconda3/envs/dsci100/lib/python3.9/importlib/__init__.py:127, in import_module(name, package)

126 level += 1

--> 127 return _bootstrap._gcd_import(name[level:], package, level)

File <frozen importlib._bootstrap>:1030, in _gcd_import(name, package, level)

File <frozen importlib._bootstrap>:1007, in _find_and_load(name, import_)

File <frozen importlib._bootstrap>:984, in _find_and_load_unlocked(name, import_)

ModuleNotFoundError: No module named 'openpyxl'

During handling of the above exception, another exception occurred:

ImportError Traceback (most recent call last)

Input In [11], in <cell line: 1>()

----> 1 canlang_data = pd.read_excel("data/can_lang.xlsx")

2 canlang_data

File /opt/miniconda3/envs/dsci100/lib/python3.9/site-packages/pandas/util/_decorators.py:311, in deprecate_nonkeyword_arguments.<locals>.decorate.<locals>.wrapper(*args, **kwargs)

305 if len(args) > num_allow_args:

306 warnings.warn(

307 msg.format(arguments=arguments),

308 FutureWarning,

309 stacklevel=stacklevel,

310 )

--> 311 return func(*args, **kwargs)

File /opt/miniconda3/envs/dsci100/lib/python3.9/site-packages/pandas/io/excel/_base.py:457, in read_excel(io, sheet_name, header, names, index_col, usecols, squeeze, dtype, engine, converters, true_values, false_values, skiprows, nrows, na_values, keep_default_na, na_filter, verbose, parse_dates, date_parser, thousands, decimal, comment, skipfooter, convert_float, mangle_dupe_cols, storage_options)

455 if not isinstance(io, ExcelFile):

456 should_close = True

--> 457 io = ExcelFile(io, storage_options=storage_options, engine=engine)

458 elif engine and engine != io.engine:

459 raise ValueError(

460 "Engine should not be specified when passing "

461 "an ExcelFile - ExcelFile already has the engine set"

462 )

File /opt/miniconda3/envs/dsci100/lib/python3.9/site-packages/pandas/io/excel/_base.py:1419, in ExcelFile.__init__(self, path_or_buffer, engine, storage_options)

1416 self.engine = engine

1417 self.storage_options = storage_options

-> 1419 self._reader = self._engines[engine](self._io, storage_options=storage_options)

File /opt/miniconda3/envs/dsci100/lib/python3.9/site-packages/pandas/io/excel/_openpyxl.py:524, in OpenpyxlReader.__init__(self, filepath_or_buffer, storage_options)

509 def __init__(

510 self,

511 filepath_or_buffer: FilePath | ReadBuffer[bytes],

512 storage_options: StorageOptions = None,

513 ) -> None:

514 """

515 Reader using openpyxl engine.

516

(...)

522 passed to fsspec for appropriate URLs (see ``_get_filepath_or_buffer``)

523 """

--> 524 import_optional_dependency("openpyxl")

525 super().__init__(filepath_or_buffer, storage_options=storage_options)

File /opt/miniconda3/envs/dsci100/lib/python3.9/site-packages/pandas/compat/_optional.py:141, in import_optional_dependency(name, extra, errors, min_version)

139 except ImportError:

140 if errors == "raise":

--> 141 raise ImportError(msg)

142 else:

143 return None

ImportError: Missing optional dependency 'openpyxl'. Use pip or conda to install openpyxl.

If the .xlsx file has multiple sheets, you have to use the sheet_name argument

to specify the sheet number or name. You can also specify cell ranges using the

usecols argument(Example: usecols="A:D" for including cells from A to D).

This functionality is useful when a single sheet contains

multiple tables (a sad thing that happens to many Excel spreadsheets since this

makes reading in data more difficult).

As with plain text files, you should always explore the data file before importing it into Python. Exploring the data beforehand helps you decide which arguments you need to load the data into Python successfully. If you do not have the Excel program on your computer, you can use other programs to preview the file. Examples include Google Sheets and Libre Office.

In Table 2 we summarize the read_* functions we covered

in this chapter. We also include the read_csv2 function for data separated by

semicolons ;, which you may run into with data sets where the decimal is

represented by a comma instead of a period (as with some data sets from

European countries).

Data File Type |

Python Function |

Python Package |

|---|---|---|

Comma ( |

|

|

Tab ( |

|

|

Semicolon ( |

|

|

Various formats ( |

|

|

Excel files ( |

|

|

Reading data from a database¶

Another very common form of data storage is the relational database. Databases \index{database} are great when you have large data sets or multiple users working on a project. There are many relational database management systems, such as SQLite, MySQL, PostgreSQL, Oracle, and many more. These different relational database management systems each have their own advantages and limitations. Almost all employ SQL (structured query language) to obtain data from the database. But you don’t need to know SQL to analyze data from a database; several packages have been written that allow you to connect to relational databases and use the Python programming language to obtain data. In this book, we will give examples of how to do this using Python with SQLite and PostgreSQL databases.

Reading data from a SQLite database¶

SQLite \index{database!SQLite} is probably the simplest relational database system

that one can use in combination with Python. SQLite databases are self-contained and

usually stored and accessed locally on one computer. Data is usually stored in

a file with a .db extension. Similar to Excel files, these are not plain text

files and cannot be read in a plain text editor.

The first thing you need to do to read data into Python from a database is to

connect to the database. We do that using the create_engine function from the

sal (SQLAlchemy) package. \index{database!connect} This does not read

in the data, but simply tells Python where the database is and opens up a

communication channel that Python can use to send SQL commands to the database.

import sqlalchemy as sal

from sqlalchemy import create_engine, select, MetaData, Table

db = sal.create_engine("sqlite:///data/can_lang.db")

conn = db.connect()

Often relational databases have many tables; thus, in order to retrieve

data from a database, you need to know the name of the table

in which the data is stored. You can get the names of

all the tables in the database using the table_names \index{database!tables}

function:

tables = db.table_names()

tables

['can_lang']

The table_names function returned only one name, which tells us

that there is only one table in this database. To reference a table in the

database (so that we can perform operations like selecting columns and filtering rows), we

use the select function \index{database!tbl} from the sqlalchemy package. The object returned

by the select function \index{dbplyr|see{database}}\index{database!dbplyr} allows us to work with data

stored in databases as if they were just regular data frames; but secretly, behind

the scenes, sqlalchemy is turning your function calls (e.g., select)

into SQL queries! To access the table in the database, we first declare the metadata of the table using

sqlalchemy package and then access the table using select function from sqlalchemy package.

metadata = MetaData(bind=None)

table = Table(

'can_lang',

metadata,

autoload=True,

autoload_with=db

)

query = select([table])

canlang_data_db = conn.execute(query)

canlang_data_db

<sqlalchemy.engine.cursor.LegacyCursorResult at 0x11061e670>

Although it looks like we just got a data frame from the database, we didn’t!

It’s a reference; the data is still stored only in the SQLite database. The output

is a CursorResult(indicating that Python does not know how many rows

there are in total!) object.

In order to actually retrieve this data in Python,

we use the fetchall() function. \index{filter}The

sqlalchemy package works this way because databases are often more efficient at selecting, filtering

and joining large data sets than Python. And typically the database will not even

be stored on your computer, but rather a more powerful machine somewhere on the

web. So Python is lazy and waits to bring this data into memory until you explicitly

tell it to using the fetchall \index{database!collect} function. The fetchall function returns the

result of the query in the form of a list, where each row in the table is an element in the list.

Let’s look at the first 10 rows in the table.

canlang_data_db = conn.execute(query).fetchall()

canlang_data_db[:10]

[('Aboriginal languages', 'Aboriginal languages, n.o.s.', 590.0, 235.0, 30.0, 665.0),

('Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages', 'Afrikaans', 10260.0, 4785.0, 85.0, 23415.0),

('Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages', 'Afro-Asiatic languages, n.i.e.', 1150.0, 445.0, 10.0, 2775.0),

('Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages', 'Akan (Twi)', 13460.0, 5985.0, 25.0, 22150.0),

('Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages', 'Albanian', 26895.0, 13135.0, 345.0, 31930.0),

('Aboriginal languages', 'Algonquian languages, n.i.e.', 45.0, 10.0, 0.0, 120.0),

('Aboriginal languages', 'Algonquin', 1260.0, 370.0, 40.0, 2480.0),

('Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages', 'American Sign Language', 2685.0, 3020.0, 1145.0, 21930.0),

('Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages', 'Amharic', 22465.0, 12785.0, 200.0, 33670.0),

('Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages', 'Arabic', 419890.0, 223535.0, 5585.0, 629055.0)]

We can look at the SQL commands that are sent to the database when we write

conn.execute(query).fetchall() in Python with the query.compile function from the

sqlalchemy package. \index{database!show_query}

compiled = query.compile(db, compile_kwargs={"render_postcompile": True})

print(str(compiled) % compiled.params)

SELECT can_lang.category, can_lang.language, can_lang.mother_tongue, can_lang.most_at_home, can_lang.most_at_work, can_lang.lang_known

FROM can_lang

The output above shows the SQL code that is sent to the database. When we

write conn.execute(query).fetchall() in Python, in the background, the function is

translating the Python code into SQL, sending that SQL to the database, and then translating the

response for us. So sqlalchemy does all the hard work of translating from Python to SQL and back for us;

we can just stick with Python!

With our canlang_data_db table reference for the 2016 Canadian Census data in hand, we

can mostly continue onward as if it were a regular data frame. For example,

we can use the select function along with where function

to obtain only certain rows. Below we filter the data to include only Aboriginal languages using

the where function of sqlalchemy

query = select([table]).where(table.columns.category == 'Aboriginal languages')

result_proxy = conn.execute(query)

result_proxy

<sqlalchemy.engine.cursor.LegacyCursorResult at 0x113650850>

Above you can again see that this data is not actually stored in Python yet:

the output is a CursorResult(indicating that Python does not know how many rows

there are in total!) object.

In order to actually retrieve this data in Python as a data frame,

we again use the fetchall() function. \index{filter}

Below you will see that after running fetchall(), Python knows that the retrieved

data has 67 rows, and there is no CursorResult object listed any more. We will display only the first 10

rows of the table from the list returned by the query.

aboriginal_lang_data_db = result_proxy.fetchall()

aboriginal_lang_data_db[:10]

[('Aboriginal languages', 'Aboriginal languages, n.o.s.', 590.0, 235.0, 30.0, 665.0),

('Aboriginal languages', 'Algonquian languages, n.i.e.', 45.0, 10.0, 0.0, 120.0),

('Aboriginal languages', 'Algonquin', 1260.0, 370.0, 40.0, 2480.0),

('Aboriginal languages', 'Athabaskan languages, n.i.e.', 50.0, 10.0, 0.0, 85.0),

('Aboriginal languages', 'Atikamekw', 6150.0, 5465.0, 1100.0, 6645.0),

('Aboriginal languages', "Babine (Wetsuwet'en)", 110.0, 20.0, 10.0, 210.0),

('Aboriginal languages', 'Beaver', 190.0, 50.0, 0.0, 340.0),

('Aboriginal languages', 'Blackfoot', 2815.0, 1110.0, 85.0, 5645.0),

('Aboriginal languages', 'Carrier', 1025.0, 250.0, 15.0, 2100.0),

('Aboriginal languages', 'Cayuga', 45.0, 10.0, 10.0, 125.0)]

sqlalchemy provides many more functions (not just select, where)

that you can use to directly feed the database reference (aboriginal_lang_data_db) into

downstream analysis functions (e.g., altair for data visualization).

But sqlalchemy does not provide every function that we need for analysis;

we do eventually need to call fetchall.

Does the result returned by fetchall function store it as a dataframe? Let’s look

what happens when we try to use shape to count rows in a dataframe \index{nrow}

aboriginal_lang_data_db.shape

## AttributeError: 'list' object has no attribute 'shape'

or tail to preview the last six rows of a data frame:

\index{tail}

aboriginal_lang_data_db.tail(6)

## AttributeError: 'list' object has no attribute 'tail'

Oops! We cannot treat the result as a dataframe, hence we need to convert it

to a dataframe after calling fetchall function

aboriginal_lang_data_db = pd.DataFrame(aboriginal_lang_data_db, columns=['category', 'language', 'mother_tongue', 'most_at_home', 'most_at_work', 'lang_known'])

aboriginal_lang_data_db.shape

(67, 6)

Additionally, some operations will not work to extract columns or single values from the reference. Thus, once you have finished your data wrangling of the database reference object, it is advisable to bring it into Python using

fetchalland then converting it into the dataframe usingpandaspackage. But be very careful usingfetchall: databases are often very big, and reading an entire table into Python might take a long time to run or even possibly crash your machine. So make sure you usewhereandselecton the database table to reduce the data to a reasonable size before usingfetchallto read it into Python!

Reading data from a PostgreSQL database¶

PostgreSQL (also called Postgres) \index{database!PostgreSQL} is a very popular

and open-source option for relational database software.

Unlike SQLite,

PostgreSQL uses a client–server database engine, as it was designed to be used

and accessed on a network. This means that you have to provide more information

to Python when connecting to Postgres databases. The additional information that you

need to include when you call the create_engine function is listed below:

dbname: the name of the database (a single PostgreSQL instance can host more than one database)host: the URL pointing to where the database is locatedport: the communication endpoint between Python and the PostgreSQL database (usually5432)user: the username for accessing the databasepassword: the password for accessing the database

Additionally, we must use the pgdb package instead of sqlalchemy in the

create_engine function call. Below we demonstrate how to connect to a version of

the can_mov_db database, which contains information about Canadian movies.

Note that the host (fakeserver.stat.ubc.ca), user (user0001), and

password (abc123) below are not real; you will not actually

be able to connect to a database using this information.

pip install pgdb

Requirement already satisfied: pgdb in /opt/miniconda3/envs/dsci100/lib/python3.9/site-packages (0.0.11)

Requirement already satisfied: psycopg2-binary>=2.8.2 in /opt/miniconda3/envs/dsci100/lib/python3.9/site-packages (from pgdb) (2.9.3)

Note: you may need to restart the kernel to use updated packages.

# !pip install pgdb

import pgdb

import sqlalchemy

from sqlalchemy import create_engine

# connection_str = "postgresql://<USERNAME>:<PASSWORD>@<IP_ADDRESS>:<PORT>/<DATABASE_NAME>"

connection_str = "postgresql://user0001:abc123@fakeserver.stat.ubc.ca:5432/can_mov_db"

db = create_engine(connection_str)

conn_mov_data = db.connect()

After opening the connection, everything looks and behaves almost identically

to when we were using an SQLite database in Python. For example, we can again use

table_names to find out what tables are in the can_mov_db database:

tables = conn_mov_data.table_names()

tables

['themes', 'medium', 'titles', 'title_aliases', 'forms', 'episodes', 'names', 'names_occupations', 'occupation', 'ratings']

We see that there are 10 tables in this database. Let’s first look at the

"ratings" table to find the lowest rating that exists in the can_mov_db

database. To access the table’s contents we first need to declare the metadata of the table

and store it in a variable named ratings. Then, we can use the select function to

refer to the data in the table and return the result in python using fetchall function, just like

we did for the SQLite database.

metadata = MetaData(bind=None)

ratings = Table(

'ratings',

metadata,

autoload=True,

autoload_with=db

)

query = select([ratings])

ratings_proxy = conn_mov_data.execute(query).fetchall()

[('The Grand Seduction', 6.6, 150),

('Rhymes for Young Ghouls', 6.3, 1685),

('Mommy', 7.5, 1060),

('Incendies', 6.1, 1101),

('Bon Cop, Bad Cop', 7.0, 894),

('Goon', 5.5, 1111),

('Monsieur Lazhar', 5.6,610),

('What if', 5.3, 1401),

('The Barbarian Invations', 5.8, 99

('Away from Her', 6.9, 2311)]

To find the lowest rating that exists in the data base, we first need to

extract the average_rating column using select:

\index{select}

avg_rating_db = select([ratings.columns.average_rating])

avg_rating_db

[(6.6,),

(6.3,),

(7.5,),

(6.1,),

(7.0,),

(5.5,),

(5.6,),

(5.4,),

(5.8,),

(6.9,)]

Next we use min to find the minimum rating in that column:

\index{min}

min(avg_rating_db)

(1.0,)

We see the lowest rating given to a movie is 1, indicating that it must have been a really bad movie…

Why should we bother with databases at all?¶

Opening a database \index{database!reasons to use} stored in a .db file

involved a lot more effort than just opening a .csv, or any of the

other plain text or Excel formats. It was a bit of a pain to use a database in

that setting since we had to use sqlalchemy to translate pandas-like

commands (where, select, etc.) into SQL commands that the database

understands. Not all pandas commands can currently be translated with

SQLite databases. For example, we can compute a mean with an SQLite database

but can’t easily compute a median. So you might be wondering: why should we use

databases at all?

Databases are beneficial in a large-scale setting:

They enable storing large data sets across multiple computers with backups.

They provide mechanisms for ensuring data integrity and validating input.

They provide security and data access control.

They allow multiple users to access data simultaneously and remotely without conflicts and errors. For example, there are billions of Google searches conducted daily in 2021 [@googlesearches]. Can you imagine if Google stored all of the data from those searches in a single

.csvfile!? Chaos would ensue!

Writing data from Python to a .csv file¶

At the middle and end of a data analysis, we often want to write a data frame

that has changed (either through filtering, selecting, mutating or summarizing)

to a file to share it with others or use it for another step in the analysis.

The most straightforward way to do this is to use the to_csv function

\index{write function!write_csv} from the pandas package. The default

arguments for this file are to use a comma (,) as the delimiter and include

column names. Below we demonstrate creating a new version of the Canadian

languages data set without the official languages category according to the

Canadian 2016 Census, and then writing this to a .csv file:

no_official_lang_data = canlang_data[canlang_data['category'] != 'Official languages']

no_official_lang_data.to_csv("data/no_official_languages.csv")

Obtaining data from the web¶

Note: This section is not required reading for the remainder of the textbook. It is included for those readers interested in learning a little bit more about how to obtain different types of data from the web.

Data doesn’t just magically appear on your computer; you need to get it from

somewhere. Earlier in the chapter we showed you how to access data stored in a

plain text, spreadsheet-like format (e.g., comma- or tab-separated) from a web

URL using one of the read_* functions from the tidyverse. But as time goes

on, it is increasingly uncommon to find data (especially large amounts of data)

in this format available for download from a URL. Instead, websites now often

offer something known as an application programming interface

(API), \index{application programming interface|see{API}}\index{API} which

provides a programmatic way to ask for subsets of a data set. This allows the

website owner to control who has access to the data, what portion of the

data they have access to, and how much data they can access. Typically, the

website owner will give you a token (a secret string of characters somewhat

like a password) that you have to provide when accessing the API.

Another interesting thought: websites themselves are data! When you type a URL into your browser window, your browser asks the web server (another computer on the internet whose job it is to respond to requests for the website) to give it the website’s data, and then your browser translates that data into something you can see. If the website shows you some information that you’re interested in, you could create a data set for yourself by copying and pasting that information into a file. This process of taking information directly from what a website displays is called \index{web scraping} web scraping (or sometimes screen scraping). Now, of course, copying and pasting information manually is a painstaking and error-prone process, especially when there is a lot of information to gather. So instead of asking your browser to translate the information that the web server provides into something you can see, you can collect that data programmatically—in the form of hypertext markup language (HTML) \index{hypertext markup language|see{HTML}}\index{cascading style sheet|see{CSS}}\index{CSS}\index{HTML} and cascading style sheet (CSS) code—and process it to extract useful information. HTML provides the basic structure of a site and tells the webpage how to display the content (e.g., titles, paragraphs, bullet lists etc.), whereas CSS helps style the content and tells the webpage how the HTML elements should be presented (e.g., colors, layouts, fonts etc.).

This subsection will show you the basics of both web scraping

with the rvest R package [@rvest]

and accessing the Twitter API

using the rtweet R package [@rtweet].

Web scraping¶

HTML and CSS selectors {-}¶

When you enter a URL into your browser, your browser connects to the web server at that URL and asks for the source code for the website. This is the data that the browser translates \index{web scraping}\index{HTML!selector}\index{CSS!selector} into something you can see; so if we are going to create our own data by scraping a website, we have to first understand what that data looks like! For example, let’s say we are interested in knowing the average rental price (per square foot) of the most recently available one-bedroom apartments in Vancouver on Craiglist. When we visit the Vancouver Craigslist website \index{Craigslist} and search for one-bedroom apartments, we should see something similar to Figure @ref(fig:craigslist-human).

Based on what our browser shows us, it’s pretty easy to find the size and price for each apartment listed. But we would like to be able to obtain that information using R, without any manual human effort or copying and pasting. We do this by examining the source code that the web server actually sent our browser to display for us. We show a snippet of it below; the entire source is included with the code for this book:

<!-- <span class="result-meta"> -->

<!-- <span class="result-price">$800</span> -->

<!-- <span class="housing"> -->

<!-- 1br - -->

<!-- </span> -->

<!-- <span class="result-hood"> (13768 108th Avenue)</span> -->

<!-- <span class="result-tags"> -->

<!-- <span class="maptag" data-pid="6786042973">map</span> -->

<!-- </span> -->

<!-- <span class="banish icon icon-trash" role="button"> -->

<!-- <span class="screen-reader-text">hide this posting</span> -->

<!-- </span> -->

<!-- <span class="unbanish icon icon-trash red" role="button" aria-hidden -->

<!-- <a href="#" class="restore-link"> -->

<!-- <span class="restore-narrow-text">restore</span> -->

<!-- <span class="restore-wide-text">restore this posting</span> -->

<!-- </a> -->

<!-- </span> -->

<!-- </p> -->

<!-- </li> -->

<!-- <li class="result-row" data-pid="6788463837"> -->

<!-- <a href="https://vancouver.craigslist.org/nvn/apa/d/north-vancouver-luxu -->

<!-- <span class="result-price">$2285</span> -->

<!-- </a> -->

Oof…you can tell that the source code for a web page is not really designed for humans to understand easily. However, if you look through it closely, you will find that the information we’re interested in is hidden among the muck. For example, near the top of the snippet above you can see a line that looks like

<span class="result-price">$800</span>

That is definitely storing the price of a particular apartment. With some more investigation, you should be able to find things like the date and time of the listing, the address of the listing, and more. So this source code most likely contains all the information we are interested in!

Let’s dig into that line \index{HTML!tag} above a bit more. You can see that

that bit of code has an opening tag (words between < and >, like

<span>) and a closing tag (the same with a slash, like </span>). HTML

source code generally stores its data between opening and closing tags like

these. Tags are keywords that tell the web browser how to display or format

the content. Above you can see that the information we want ($800) is stored

between an opening and closing tag (<span> and </span>). In the opening

tag, you can also see a very useful “class” (a special word that is sometimes

included with opening tags): class="result-price". Since we want R to

programmatically sort through all of the source code for the website to find

apartment prices, maybe we can look for all the tags with the "result-price"

class, and grab the information between the opening and closing tag. Indeed,

take a look at another line of the source snippet above:

<span class="result-price">$2285</span>

It’s yet another price for an apartment listing, and the tags surrounding it

have the "result-price" class. Wonderful! Now that we know what pattern we

are looking for—a dollar amount between opening and closing tags that have the

"result-price" class—we should be able to use code to pull out all of the

matching patterns from the source code to obtain our data. This sort of “pattern”

is known as a CSS selector (where CSS stands for cascading style sheet).

The above was a simple example of “finding the pattern to look for”; many

websites are quite a bit larger and more complex, and so is their website

source code. Fortunately, there are tools available to make this process

easier. For example,

SelectorGadget is

an open-source tool that simplifies identifying the generating

and finding of CSS selectors.

At the end of the chapter in the additional resources section, we include a link to

a short video on how to install and use the SelectorGadget tool to

obtain CSS selectors for use in web scraping.

After installing and enabling the tool, you can click the

website element for which you want an appropriate selector. For

example, if we click the price of an apartment listing, we

find that SelectorGadget shows us the selector .result-price

in its toolbar, and highlights all the other apartment

prices that would be obtained using that selector (Figure @ref(fig:sg1)).

If we then click the size of an apartment listing, SelectorGadget shows us

the span selector, and highlights many of the lines on the page; this indicates that the

span selector is not specific enough to capture only apartment sizes (Figure @ref(fig:sg3)).

To narrow the selector, we can click one of the highlighted elements that

we do not want. For example, we can deselect the “pic/map” links,

resulting in only the data we want highlighted using the .housing selector (Figure @ref(fig:sg2)).

So to scrape information about the square footage and rental price

of apartment listings, we need to use

the two CSS selectors .housing and .result-price, respectively.

The selector gadget returns them to us as a comma-separated list (here

.housing , .result-price), which is exactly the format we need to provide to

R if we are using more than one CSS selector.

Stop! Are you allowed to scrape that website?

Before scraping \index{web scraping!permission} data from the web, you should always check whether or not

you are allowed to scrape it! There are two documents that are important

for this: the robots.txt file and the Terms of Service

document. If we take a look at Craigslist’s Terms of Service document,

we find the following text: “You agree not to copy/collect CL content

via robots, spiders, scripts, scrapers, crawlers, or any automated or manual equivalent (e.g., by hand).”

So unfortunately, without explicit permission, we are not allowed to scrape the website.

What to do now? Well, we could ask the owner of Craigslist for permission to scrape. However, we are not likely to get a response, and even if we did they would not likely give us permission. The more realistic answer is that we simply cannot scrape Craigslist. If we still want to find data about rental prices in Vancouver, we must go elsewhere. To continue learning how to scrape data from the web, let’s instead scrape data on the population of Canadian cities from Wikipedia. \index{Wikipedia} We have checked the Terms of Service document, and it does not mention that web scraping is disallowed. We will use the SelectorGadget tool to pick elements that we are interested in (city names and population counts) and deselect others to indicate that we are not interested in them (province names), as shown in Figure @ref(fig:sg4).

We include a link to a short video tutorial on this process at the end of the chapter in the additional resources section. SelectorGadget provides in its toolbar the following list of CSS selectors to use:

td:nth-child(5),

td:nth-child(7),

.infobox:nth-child(122) td:nth-child(1),

.infobox td:nth-child(3)

Now that we have the CSS selectors that describe the properties of the elements

that we want to target (e.g., has a tag name price), we can use them to find

certain elements in web pages and extract data.

Using rvest

Now that we have our CSS selectors we can use the rvest R package \index{rvest} to scrape our

desired data from the website. We start by loading the rvest package:

library(rvest)

Next, we tell R what page we want to scrape by providing the webpage’s URL in quotations to the function read_html:

page <- read_html("https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Canada")

The read_html function \index{read function!read_html} directly downloads the source code for the page at

the URL you specify, just like your browser would if you navigated to that site. But

instead of displaying the website to you, the read_html function just returns

the HTML source code itself, which we have

stored in the page variable. Next, we send the page object to the html_nodes

function, along with the CSS selectors we obtained from

the SelectorGadget tool. Make sure to surround the selectors with quotation marks; the function, html_nodes, expects that

argument is a string. The html_nodes function then selects nodes from the HTML document that

match the CSS selectors you specified. A node is an HTML tag pair (e.g.,

<td> and </td> which defines the cell of a table) combined with the content

stored between the tags. For our CSS selector td:nth-child(5), an example

node that would be selected would be:

<td style="text-align:left;background:#f0f0f0;">

<a href="/wiki/London,_Ontario" title="London, Ontario">London</a>

</td>

We store the result of the html_nodes function in the population_nodes variable.

Note that below we use the paste function with a comma separator (sep=",")

to build the list of selectors. The paste function converts

elements to characters and combines the values into a list. We use this function to

build the list of selectors to maintain code readability; this avoids

having one very long line of code with the string

"td:nth-child(5),td:nth-child(7),.infobox:nth-child(122) td:nth-child(1),.infobox td:nth-child(3)"

as the second argument of html_nodes:

selectors <- paste("td:nth-child(5)",

"td:nth-child(7)",

".infobox:nth-child(122) td:nth-child(1)",

".infobox td:nth-child(3)", sep=",")

population_nodes <- html_nodes(page, selectors)

head(population_nodes)

print_html_nodes(head(population_nodes))

Next we extract the meaningful data—in other words, we get rid of the HTML code syntax and tags—from

the nodes using the html_text

function. In the case of the example

node above, html_text function returns "London".

population_text <- html_text(population_nodes)

head(population_text)

Fantastic! We seem to have extracted the data of interest from the

raw HTML source code. But we are not quite done; the data

is not yet in an optimal format for data analysis. Both the city names and

population are encoded as characters in a single vector, instead of being in a

data frame with one character column for city and one numeric column for

population (like a spreadsheet).

Additionally, the populations contain commas (not useful for programmatically

dealing with numbers), and some even contain a line break character at the end

(\n). In Chapter @ref(wrangling), we will learn more about how to wrangle data

such as this into a more useful format for data analysis using R.

Using an API¶

Rather than posting a data file at a URL for you to download, many websites these days provide an API \index{API} that must be accessed through a programming language like R. The benefit of this is that data owners have much more control over the data they provide to users. However, unlike web scraping, there is no consistent way to access an API across websites. Every website typically has its own API designed especially for its own use case. Therefore we will just provide one example of accessing data through an API in this book, with the hope that it gives you enough of a basic idea that you can learn how to use another API if needed.

In particular, in this book we will show you the basics of how to use

the rtweet package in R\index{API!rtweet}\index{rtweet}\index{Twitter} to access

data from the Twitter API. One nice feature of this particular

API is that you don’t need a special token \index{API!token} to access it; you simply need to

make an account with them. Your access to the data will then be authenticated and controlled through

your account username and password. If you have a Twitter

account already (or are willing to make one), you can follow

along with the examples that we show here. To get started, load the rtweet package:

library(rtweet)

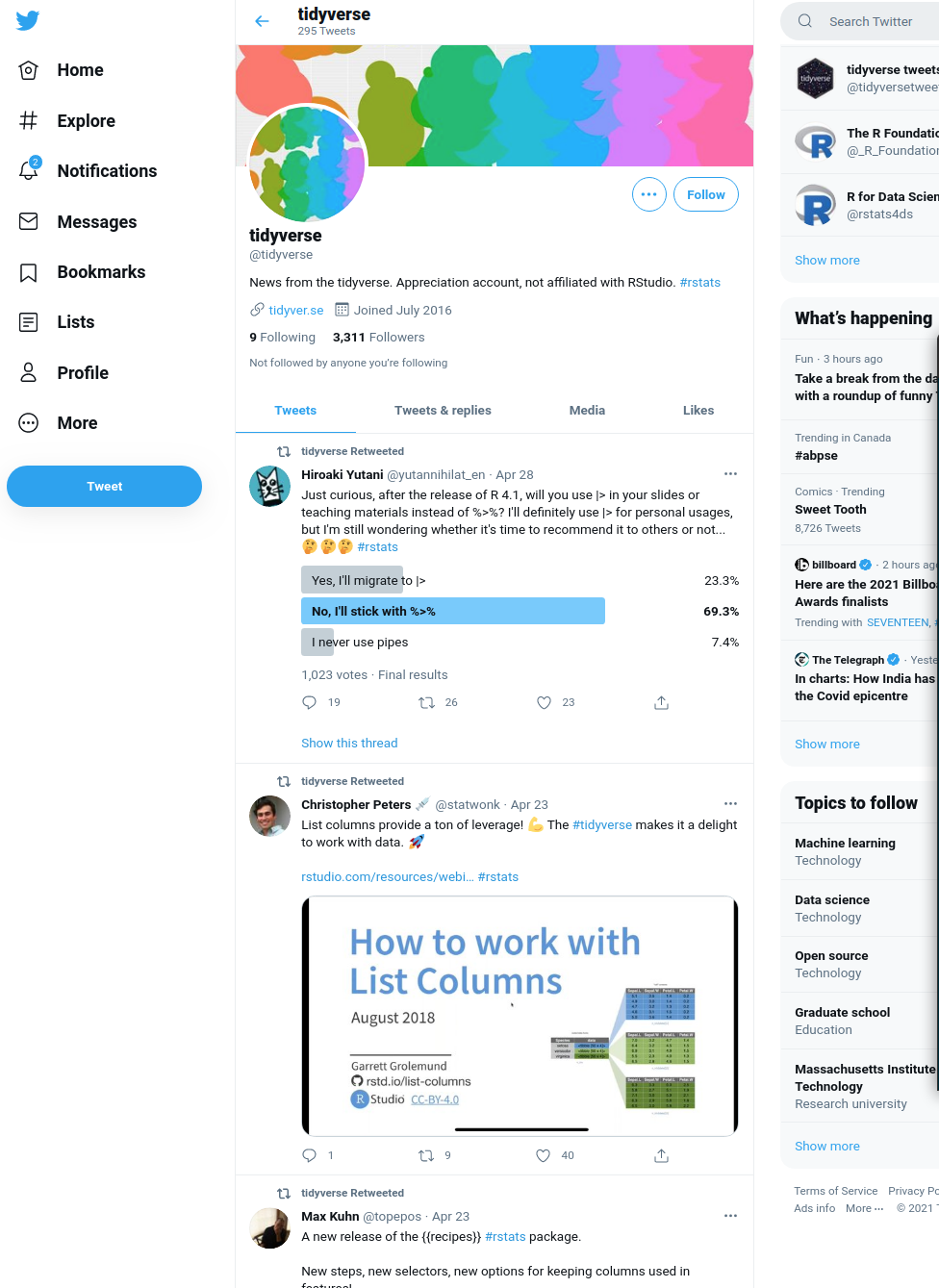

This package provides an extensive set of functions to search Twitter for tweets, users, their followers, and more. Let’s construct a small data set of the last 400 tweets and retweets from the @tidyverse account. A few of the most recent tweets are shown in Figure @ref(fig:01-tidyverse-twitter).

Fig. 10 The tidyverse account Twitter feed.¶

Stop! Think about your API usage carefully!

When you access an API, you are initiating a transfer of data from a web server to your computer. Web servers are expensive to run and do not have infinite resources. If you try to ask for too much data at once, you can use up a huge amount of the server’s bandwidth. If you try to ask for data too frequently—e.g., if you make many requests to the server in quick succession—you can also bog the server down and make it unable to talk to anyone else. Most servers have mechanisms to revoke your access if you are not careful, but you should try to prevent issues from happening in the first place by being extra careful with how you write and run your code. You should also keep in mind that when a website owner grants you API access, they also usually specify a limit (or quota) of how much data you can ask for. Be careful not to overrun your quota! In this example, we should take a look at the Twitter website to see what limits we should abide by when using the API.

Using rtweet

After checking the Twitter website, it seems like asking for 400 tweets one time is acceptable.

So we can use the get_timelines function to ask for the last 400 tweets from the @tidyverse account.

tidyverse_tweets <- get_timelines('tidyverse', n=400)

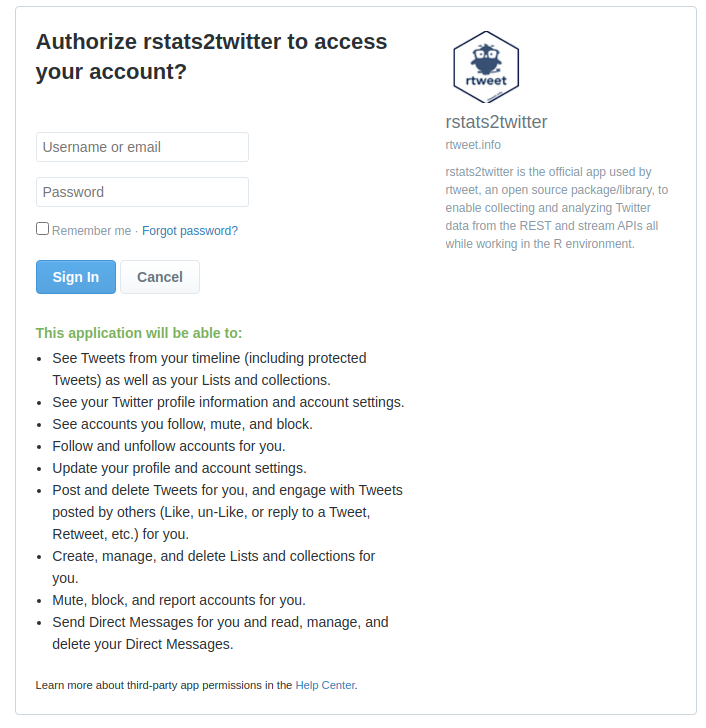

When you call the get_timelines for the first time (or any other rtweet function that accesses the API),

you will see a browser pop-up that looks something like Figure @ref(fig:01-tidyverse-authorize).

(ref:01-tidyverse-authorize) The rtweet authorization prompt.

Fig. 11 (ref:01-tidyverse-authorize)¶

This is the rtweet package asking you to provide your own Twitter account’s login information.

When rtweet talks to the Twitter API, it uses your account information to authenticate requests;

Twitter then can keep track of how much data you’re asking for, and how frequently you’re asking.

If you want to follow along with this example using your own Twitter account, you should read

over the list of permissions you are granting rtweet very carefully and make sure you are comfortable

with it. Note that rtweet can be used to manage most aspects of your account (make posts, follow others, etc.),

which is why rtweet asks for such extensive permissions.

If you decide to allow rtweet to talk to the Twitter API using your account information, then

input your username and password and hit “Sign In.” Twitter will probably send you an email to say

that there was an unusual login attempt on your account, and in that case you will have to take

the one-time code they send you and provide that to the rtweet login page too.

Note: Every API has its own way to authenticate users when they try to access data. Many APIs require you to sign up to receive a token, which is a secret password that you input into the R package (like

rtweet) that you are using to access the API.

With the authentication setup out of the way, let’s run the get_timelines function again to actually access

the API and take a look at what was returned:

tidyverse_tweets <- get_timelines('tidyverse', n=400)

tidyverse_tweets

tidyverse_tweets <- read_csv("data/tweets.csv")

tidyverse_tweets

The data has quite a few variables! (Notice that the output above shows that we

have a data table with 293 rows and 71 columns). Let’s reduce this down to a

few variables of interest: created_at, retweet_screen_name, is_retweet,

and text.

tidyverse_tweets <- select(tidyverse_tweets,

created_at,

retweet_screen_name,

is_retweet,

text)

tidyverse_tweets

If you look back up at the image of the @tidyverse Twitter page, you will

recognize the text of the most recent few tweets in the above data frame. In

other words, we have successfully created a small data set using the Twitter

API—neat! This data is also quite different from what we obtained from web scraping;

it is already well-organized into a tidyverse data frame (although not every API

will provide data in such a nice format).

From this point onward, the tidyverse_tweets data frame is stored on your

machine, and you can play with it to your heart’s content. For example, you can use

write_csv to save it to a file and read_csv to read it into R again later;

and after reading the next few chapters you will have the skills to

compute the percentage of retweets versus tweets, find the most oft-retweeted

account, make visualizations of the data, and much more! If you decide that you want

to ask the Twitter API for more data

(see the rtweet page

for more examples of what is possible), just be mindful as usual about how much

data you are requesting and how frequently you are making requests.

Exercises¶

Practice exercises for the material covered in this chapter can be found in the accompanying worksheets repository in the “Reading in data locally and from the web” row. You can launch an interactive version of the worksheet in your browser by clicking the “launch binder” button. You can also preview a non-interactive version of the worksheet by clicking “view worksheet.” If you instead decide to download the worksheet and run it on your own machine, make sure to follow the instructions for computer setup found in Chapter @ref(move-to-your-own-machine). This will ensure that the automated feedback and guidance that the worksheets provide will function as intended.

Additional resources¶

The

readrdocumentation provides the documentation for many of the reading functions we cover in this chapter. It is where you should look if you want to learn more about the functions in this chapter, the full set of arguments you can use, and other related functions. The site also provides a very nice cheat sheet that summarizes many of the data wrangling functions from this chapter.Sometimes you might run into data in such poor shape that none of the reading functions we cover in this chapter work. In that case, you can consult the data import chapter from R for Data Science [@wickham2016r], which goes into a lot more detail about how R parses text from files into data frames.

The

hereR package [@here] provides a way for you to construct or find your files’ paths.The

readxldocumentation provides more details on reading data from Excel, such as reading in data with multiple sheets, or specifying the cells to read in.The

rioR package [@rio] provides an alternative set of tools for reading and writing data in R. It aims to be a “Swiss army knife” for data reading/writing/converting, and supports a wide variety of data types (including data formats generated by other statistical software like SPSS and SAS).A video from the Udacity course Linux Command Line Basics provides a good explanation of absolute versus relative paths.

If you read the subsection on obtaining data from the web via scraping and APIs, we provide two companion tutorial video links for how to use the SelectorGadget tool to obtain desired CSS selectors for:

The

politeR package [@polite] provides a set of tools for responsibly scraping data from websites.